From Friction to Flow: Why I'm Building Widgets for Reproducible Research

A Juptyer Widget for viewing and sorting available resources on Chameleon

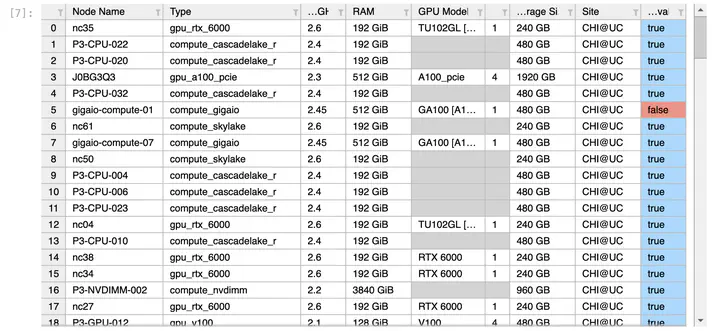

A Juptyer Widget for viewing and sorting available resources on ChameleonThis summer, I’m building Jupyter Widgets to reduce friction in reproducible workflows on Chameleon. Along the way, I’m reflecting on what usability teaches us about the real meaning of reproducibility.

Supercomputing Competition: Reproducibility Reality Check

My first reproducibility experience threw me into the deep end—trying to recreate a tsunami simulation with a GitHub repository, a scientific paper, and a lot of assumptions. I was part of a student cluster competition at the Supercomputing Conference, where one of our challenges was to reproduce the results of a prior-year paper. I assumed “reproduce” meant something like “re-run the code and get the same numbers.” But what we actually had to do was rebuild the entire computing environment from scratch—on different hardware, with different software versions, and vague documentation. I remember thinking: If all these conditions are so different, what are we really trying to learn by conducting reproducibility experiments? That experience left me with more questions than answers, and those questions have stayed with me. In fact, they’ve become central to my PhD research.

Summer of Reproducibility: Lessons from 100+ Experiments on Chameleon

I’m currently a PhD student and research software engineer exploring questions around what computational reproducibility really means, and when and why it matters. I also participated in the Summer of Reproducibility 2024, where I helped assess over 100 public experiments on the Chameleon platform. Our analysis revealed key friction points—especially around usability—that don’t necessarily prevent reproducibility in the strictest sense, but introduce barriers in terms of time, effort, and clarity. These issues may not stop an expert from reproducing an experiment, but they can easily deter others from even trying. This summer’s project is about reducing that friction—some of which I experienced firsthand—by improving the interface between researchers and the infrastructure they rely on.

From Psychology Labs to Jupyter Notebooks: Usability is Central to Reproducibility

My thinking shifted further when I was working as a research software engineer at Purdue, supporting a psychology lab that relied on a complex statistical package. For most researchers in the lab, using the tool meant wrestling with cryptic scripts and opaque parameters. So I built a simple Jupyter-based interface to help them visualize input matrices, validate settings, and run analyses without writing code. The difference was immediate: suddenly, people could actually use the tool. It wasn’t just more convenient—it made the research process more transparent and repeatable. That experience was a turning point for me. I realized that usability isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s critical for reproducibility.

Teaching Jupyter Widget Tutorials at SciPy

Since that first experience, I’ve leaned into building better interfaces for research workflows—especially using Jupyter Widgets. Over the past few years, I’ve developed and taught tutorials on how to turn scientific notebooks into interactive web apps, including at the SciPy conference in 2023 and 2024. These tutorials go beyond the basics: I focus on building real, multi-tab applications that reflect the complexity of actual research tools. Teaching others how to do this has deepened my own knowledge of the widget ecosystem and reinforced my belief that good interfaces can dramatically reduce the effort it takes to reproduce and reuse scientific code. That’s exactly the kind of usability work I’m continuing this summer—this time by improving the interface between researchers and the Chameleon platform itself.

Making Chameleon Even More Reproducible with Widgets

This summer, I’m returning to Chameleon with a more focused goal: reducing some of the friction I encountered during last year’s reproducibility project. One of Chameleon’s standout features is its Jupyter-based interface, which already goes a long way toward making reproducibility more achievable. My work builds on that strong foundation by improving and extending interactive widgets in the Python-chi library — making tasks like provisioning resources, managing leases, and tracking experiment progress on Chameleon even more intuitive. For example, instead of manually digging through IDs to find an existing lease, a widget could present your current leases in a dropdown or table, making it easier to pick up where you left off and avoid unintentionally reserving unnecessary resources. It’s a small feature, but smoothing out this kind of interaction can make the difference between someone giving up or trying again. That’s what this project is about.

Looking Ahead: Building for People, Not Just Platforms

I’m excited to spend the next few weeks digging into these questions—not just about what we can build, but how small improvements in usability can ripple outward to support more reproducible, maintainable, and accessible research. Reproducibility isn’t just about rerunning code; it’s about supporting the people who do the work. I’ll be sharing updates as the project progresses, and I’m looking forward to learning (and building) along the way. I’m incredibly grateful to once again take part in this paid experience, made possible by the 2025 Open Source Research Experience team and my mentors.